|

After lighting the little bulbs with a single battery, earlier in the week, we wondered if we could light a standard bulb, using more batteries and longer wires.

0 Comments

In a chapter entitled Hope, I expected to find more - you know - hope. The thinking in this chapter of Angela Duckworth's book, Grit, the Power of Passion and Perseverance, might turn some people's thinking upside down. The conclusion is that people who face failure, and keep getting back up after falling down, tend to be more optimistic and forward thinking than people who experience success without struggle. Enter, Carol Dweck, famous for her research about growth mindset. Duckworth refers to one of Dweck's studies in particular, in which one group of students received praise for doing well, no matter how many problems they successfully completed, and students in a second group were occasionally told they hadn't solved enough problems and they should have tried harder. What Carol found is that the children in the success only program gave up just as easily after encountering very difficult problems as they had before training. In sharp contrast, children in the attribution retraining program tried harder after encountering difficulty. Is seems as though they'd learned to interpret failure as a cue to try harder rather than as confirmation that they lacked the ability to succeed. This is in line with my own thinking. I realize we will all have our pessimistic days. We'll all slip into negativity that can get us down, sometimes for an extended time, but those failures that get us to that point can also be stepping stones to success. If we let it, getting knocked down can empower us. I like to think of a growth mindset this way: Some of us believe, deep down, that people really can change. These growth-oriented people assume that it's possible, for example, to get smarter if you're given the right opportunities and support and if you try hard enough and if you believe you can do it. Conversely, some people think you can learn skills, like how to ride a bike or do a sales pitch, but your capacity to learn skills - your talent - can't be trained. The problem with holding the latter fixed-mindset view - and many people who consider themselves talented do - is that no road is without bumps. Eventually, you're going to hit one. At that point, having a fixed mindset becomes a tremendous liability. This is when a C-, a rejection letter, a disappointing progress review at work, or any other setback can derail you. With a fixed mindset, you're likely to interpret these setbacks as evidence that, after all, you don't have "the right stuff" - you're not good enough. With a growth mindset, you believe you can learn to do better.  I must try to use the right kind of language when addressing the children in my class and my own children at home. I can be the reason they press forward, in spite of stumbling, or I can tell them they are OK. I can run to them when they fall, pick them up off the ground, and kiss their boo boos, or I can get them to stand up on their own and fix the things that caused them to fall in the first place. There is, of course, a fine line between doing the latter and being a dry-nosed, thick-skinned jerk. Once again, I defer to the idea that we must achieve balance. Mrs. Duckworth found that students come to us with either a fixed or a growth mindset. They have learned by watching the adults around them react to failure in themselves and disappointments in others. They have absorbed the mindsets and ideas from the people they have been around. And no one is immune to that absorption. The child who lives in a house of poverty is in danger of observing too much helplessness from their parents who find it hard to survive and thrive. Then, there are also those students who more naturally succeed: ...I also worry about people who cruise though life, friction-free, for a long, long time before encountering their first real failure. They have so little practice falling and getting up again... Well, we've always known that it takes all kinds to make the world go 'round.

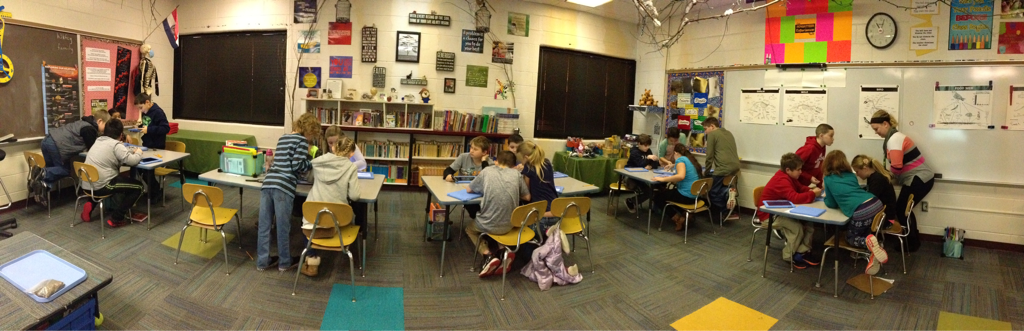

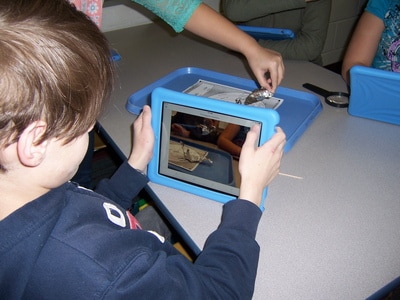

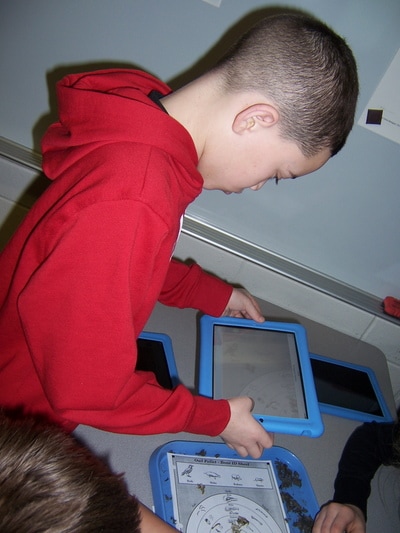

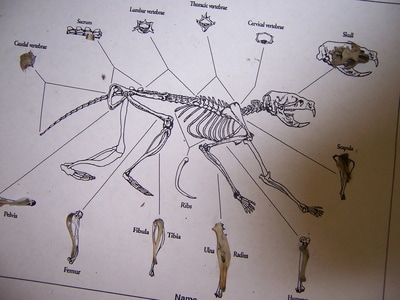

Returning to the chapter title, I realize that hope comes with effort and not with success. The more we are pressed downward, the more we are likely to reach for our goals, and the more we reach, the more we hope for those goals. Those souls who naturally succeed, with little effort, seem to have less hope since their goals are more easily fulfilled. Usually. We need to exercise our hope in order to strengthen it. Our first electricity lesson was one with experimentation. Students were challenged to find as many ways as they could to light a bulb with a single battery and a single wire. We also challenged them to find as many ways they could not light a bulb with the same supplies.

Read the sentence below. Do you see any problems? you must finish the assignment by yourself the teacher instructed Do not rewrite the sentence. In fact, don't even fix the sentence. Instead, on your paper, tell the writer how to correct three things.

Read the sentence below. Do you see any problems? you has to keep trying or you wont never succeed Do not rewrite the sentence. In fact, don't even fix the sentence. Instead, on your paper, tell the writer how to correct three things.

"We are all born ignorant,

but one must work hard to remain stupid." (Benjamin Franklin) "He who asks a question is a fool for five minutes; he who does not ask a question is a fool forever. We are all born ignorant, but to stay ignorant is a choice; without some form of education you are lost." (Chinese Proverb) "Men are born ignorant, not stupid. They are made stupid by education." (Bertrand Russell) Interest is one source of passion. Purpose - the intention to contribute to the well-being of others - is another. The mature passions of gritty people depend on both.  In the words of the logical Mr. Spock, "Fascinating." In fact, even Spock understands the idea that working with others in mind is logical, famously telling Captain Kirk, "The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few." I'm pretty sure that's now always true, but for the purpose of illustration, I'll go with it. Angela Duckworth wrote the book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. In her book, she shares her research on how to be gritty. In subsequent chapters, she identifies interest and purpose as motivating factors. At the same time, she explains that interest and purpose are independent. They can both be lacking, they can both be wholly present, and one may appear without the other. But we don't have to get into all of that in order to understand the big picture - that when other people benefit from what one does, one becomes grittier. When I talk to grit paragons, and they tell me that what they're pursuing has purpose, they mean something much deeper than mere intention. They're not just goal-oriented; the nature of their goals is special. As an educator, I can see that. Almost every list of gritty people could have teachers in it. But grittiness extends to many professions we may not consider including. Duckworth reminds us of everyone's importance: Consider the parable of the bricklayers: I can't say I've always been a passionate teacher. There have certainly been days, months, even years, when teaching has been a job. Even more so, I have considered teaching to be a career. Thankfully, there are many days, months, and years that I have felt like teaching is a calling. I don't necessarily like that term, though: I would rather revert to the word passion. So does that mean that we can freely move between the three? Does that mean that grittiness can be developed? I am thankful that the answer to both of these questions is yes. In other words, a bricklayer who one day says, "I am laying bricks" might at some point become the bricklayer who recognizes "I am building the house of God."  Likewise, I suppose, my service to other people might just be less noble. Before I was a teacher, I managed an outdoor recreational facility known as The Wilds. The Wilds family owned the property which catered to people who liked to be outside doing "rustic" activities like fishing, horseback riding, and roasting hotdogs. Part of my job included making schedules for the employees. I tried to stay active, as well. My job was not just to delegate, but to lead by example. When folks, for instance, visited our ten-acre lake or a smaller pond, to wet their fishing line, we charged by the pound for the fish they caught. They could pay and take their stringers, or they could choose to have their fish processed in a little facility that we lovingly called the "Skinnin' Shed", named because we stocked the waters with grain-fed channel catfish. Nobody every thought that I would have a job as a fish skinner, but when other employees were not available to wield the knives and pliers, the task fell to me. Visitors enjoyed watching the process of skinning a catfish, and I liked putting on a show. I made up songs to go along with it, and my knife flew like the table cook at a Japanese restaurant. I suppose, in some weird way, I was performing a service. There were smiles and conversation as people were amazed that I could skin and filet a catfish in 30-40 seconds. The point is that this was not the ultimate job at The Wilds. As the manager, I was poised to develop as the company grew. But that was the 1980s, and banks were calling in their loans. The Wilds had made a significant investment to bring a train to the property, and the company ultimately failed because they couldn't pay on the loan early. I would not be a teacher today if things had gone as dreamed. Being a leader in the tourist industry, at a place I envisioned as Silver Dollar City for Oklahoma, would have been awesome, but even working at starting levels was enjoyable because I was engaging with other people. Plus, the food in our restaurant was so good. Students were treated to one last Christmas game in Room 404. On the first day back, we took care of a game that was prepared but not completed during the party. As we continue to refine our blogging focus, we should consider the quality of the material we put out there. The public doesn't want to read some humdrum posts about this or that, but would be more interested in what this video describes as Wow Work. Watch and think about how your own posts can be better:

This is the way Angela Duckworth explains the psychology of interest and its development (Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance). I suppose she may be right, but then again, in my tendancy to call for balance, I must question her conclusions. I know, for instance, that when I was in second of third grade, I wanted to be a missionary. I remember thinking I could see parts of the world in doing so, and I still have a picture I drew of myself preaching as a missionary on foreign soil. It was later in life that I found other interests, and the world for an adult is a scarier place than for a child (perceptions and all of that, I suppose). However, when I came to Joplin, I had a couple of opportunities to fulfill that childhood dream anyway. I traveled to Honduras on two occasions and spent over a week each time in that Central American setting (Read more about the Girl in the Blue Dress.). In high school and college, I developed some skills in public speaking, graduating with a Bachelor's degree in Communication. After some years in the tourism industry, went back to college to earn a second degree in Elementary Education. Since then, I have used my childhood dreams and my current strengths to preach in area churches and in teaching elementary school. To make a long explanation shorter, my childhood ideas for a career did affect my choices later on. I suppose that's what Duckworth explains as her third, above. So I guess I see her first as being only being true through the disclaimer lens of the third, and not wholly true by itself. It is, however, her second point that kind of gets in my craw. But again, there is explanation to go along with it, so I'm being unfair in judging the statement without its accompanying notes. Duckworth wants me to do more than just will myself to like something. She encourages me to experiment instead, pointing out that action is the key to developing interest in something. I get that point, but I think she downplays the introspection part. I can point to many times that I have jumpstarted my interest in teaching because of introspection. I constantly reflect on the ways and reasons I do things. It's the point of Joplin Schools' focus on the PDSA (Plan - Do - Study - Action) cycle. In the interest of improvement, as stakeholders, it is important to us that we constantly debrief ourselves and tweak our systems, looking forward to the next time a situation appears. The point I think we both make, in synthesis, is that interest is developed. It is molded and nurtured. It is a compilation of our life experiences and the people we hold dear and respect. Let Angela Duckworth herself punctuate this section of my reflection with following: Is it "a drag" that passions don't come to us all at once, as epiphanies, without the need to actively develop them? Maybe. But the reality is that our early interests are fragile, vaguely defined, and in need of energetic, years-long cultivation and refinement. Looking forward into the next chapter of Duckworth's book, the PDSA model becomes apparent once again. When it comes to developing interest and improving a skill, she says, practice is key. "This is how experts practice," she says: First, they set a stretch goal, zeroing in on just one narrow aspect of their overall performance. Rather than focus on what they already do well, experts strive to improve specific weaknesses. They intentionally seek out challenges they can't yet meet. That hits hard - right in the gut. The truth is, I want to focus on the things I already do well. I want to do more of those things with which I am comfortable. I don't want to do the things I'm not good at doing. Then again, that's Duckworth's point - that grit paragons work on their weaknesses. They are driven to identify and practice the things they have not perfected. Then, with undivided attention and great effort, experts strive to reach their stretch goal. Interestingly, many choose to do so while nobody's watching. I don't think that's interesting at all, Mrs. D. If I am going to work on things I am not good at doing, I probably do not want others to watch. Additionally, working alone helps me to tune other things out. I can focus better without a bunch of eyes scrutinizing every move I make. As soon as possible, experts hungrily seek feedback on how they did. Necessarily, much of that feedback is negative. This means that experts are more interested in what they did wrong - so they can fix it - than what they did right. The active processing of this feedback is essential as its immediacy. In education, we have long understood that the right kind of feedback is powerful, but we tend to struggle with the idea that we don't want to give "negative" feedback. For years, we have been fed all the lines about maintaining and fostering a student's self concept and personal pride, and we have naturally balanced all of that with the idea than anything negative can humiliate a child.

In other words, our practice - based on honest study of what we need to work on - is pivotal to improvement and mastery. We used to say, practice makes perfect, until someone came along and revised it to perfect practice makes perfect. Neither is really true. We might need a new revision: focused practice makes perfect, or perhaps well-defined practice makes perfect. Or maybe we need to define our terms a little more. At any rate, what comes next? And...then what? What follows mastery of a stretch goal? One must notice the resemblance to PDSA. The constant cycle of planning, executing, reviewing, and tweaking the things we do just makes sense, and through her studies, the author here seems to conclude the same.

Read the sentence below. Do you see any problems? coach pickler aint happy with nothin but are bestest effort Do not rewrite the sentence. In fact, don't even fix the sentence. Instead, on your paper, tell the writer how to correct three things.

I worked as a teacher intern for two summers at Tinker Air Force Base in Midwest City, Oklahoma. Every day, I would drive through the security gates to find a parking spot at the Environmental Management building on base. While there, I put together some booklets, wrote articles, recorded and edited videos, and took visitors on tours of the base with an environmental management focus. I was also able to drive electric and solar cars and attend the retirement of a high ranking Air Force general during my summer hours. I was fortunate enough to work with an older gentleman (Bill), in the multimedia section at one end of the building, while in other places, people were slotted into cubicles (though I'm not sure what those people did). As I walked through the cubicled area, my attention was often drawn to one lady's cubicle. While the rest of the office buzzed with telephone beeps and keyboard clicking, this lady's cubicle was always silent. She sat hunched over her desk with her back to the cubicle "doorway", sleeping. Everyday. Every time I passed, I wondered what this woman did. What was her actual job? And did her boss ever figure out that it wasn't getting done? Here was a person who was not interested in her job, but I'll guess that she would fight tooth-and-nail for her paycheck if it went missing. We could talk about government waste, but that's for another time.

Well, duh! I mean, do we really need to have meta-analyzed evidence that this is true? At what point does common sense kick in? Or have we lost that ability in the 21st Century? Still, it might be one of those simple things that we forget about, and it might be one of those things that we forget to teach. I am reminded that the simple things - the things I assume do not need to be taught - are the things my students need the most. I keep thinking about that woman in the environmental management office. Her disinterest in the mission clearly did not translate into performance. Duckworth points out: Second, people perform better at work when what they do interests them. This is the conclusion of another meta-analysis of sixty studies conducted over the past sixty years.  I could have saved the researchers a lot of time (and lots of money, which probably came from taxpayers) by just pointing them to this one lady in one office building. We've all see people stuck in "dead-end" jobs, but we might also recognize that those jobs are only dead ends because the people have no personal interest invested. I worked the drive-through at McDonald's one summer. When people ask why I chose to work in fast food, instead of teaching summer school or doing something more career-related, my answer to them is, "Because I wanted to." That's an honest answer, too. I had never worked in fast food, and now, as an adult, I wanted to try it out. All cards on the table, there was something in the back of my head that told me I didn't need this job. It didn't really matter if I got fired from that job, because I would be returning to the classroom in August anyway. Still, I went in with a different attitude. I was there as an observer and an example. There were, of course, many young people working on my shifts, and the manager had to constantly give them things to do. They did not seem to have the wherewithal to fill the needs of the restaurant on their own. They were perfectly capable, but chose instead to stand around or talk to each other. In the meantime, I was scrubbing the fly specks off of the menu board. I was mopping the restroom. I was cleaning trays. Not only that, but when the drive through was backed up, I would engage the people at the speaker. I was even known to offer a song once in a while. Unlike other employees, many of whom were hired one day and quit the next, I kept myself busy. I was a self-starter. I was focused on service. When I left, that summer, the managers even broke out a Ronald McDonald cake to see me off. My point here is that even if I wasn't interested in the job itself - pressing buttons on a keypad and making change to customers - I made the job interesting, and I kept myself busy. I went home tired, but not because I was bored. According to Duckworth, citing Gallup polls, "more than two-thirds of adults said they were not engaged at work, a good portion of which were 'actively disengaged'." In fact, worldwide, only 13 percent of adults call themselves "engaged" at work. "So," concludes Duckworth, ""it seems that very few people end up loving what they do for a living. Shouldn't this concern every conscientious educator? In an interview with psychology professor Barry Schwartz, Mrs. Duckworth found his explanation compelling: A related problem, Barry says, is the mythology that falling in love with a career should be sudden and swift: "There are a lot of things where the subtleties and exhilerations come with sticking with it for a while, getting elbow-deep into something. A lot of things seems uninteresting and superficial until you start doing them and, after a while, you realize that there are som many facets you didn't know at the start, and you never can fully solve the problem, or fully understand it, or what have you. Well, that requires that you stick with it." In other words, we can learn to like things in which we previously held no interest. That can be a challenge for a teacher: what do I do to nurture interest in a variety of skills and lessons for every student? There must be more to the psychology of interests, and I am drawn into the conversation as I read further in this chapter of Grit, in which I - and you - might become perplexed and frustrated, with statements such as this one - A seventh grader is just beginning to figure out her general likes and dislikes. Now, what am I, a fourth grade teacher, supposed to do with that. Thanks for the teaser, Angela. You have my attention, and I will read on in hopes of gleaning from your wisdom and research.

|

AnthemThe Hoggatteer Revolution

is an extensive, award-winning, inimitable, digital platform for Encouraging and Developing the Arts, Sciences, and honest Christianity in the beautiful, friendly LAND OF THE FREE AND THE HOME OF THE BRAVE This site is described as

"a fantastic site... chockablock full of interesting ideas, hilarious anecdotes, and useful resources."

...to like, bookmark, pin,

tweet, and share about the site... and check in regularly for new material, posted often before DAWN'S EARLY LIGHT! History in ResidenceElementary Schools: Bring Mr. Hoggatt into your classroom for a week of engaging and rigorous history programming with your students. LEARN MORE BUILDING BETTER

|