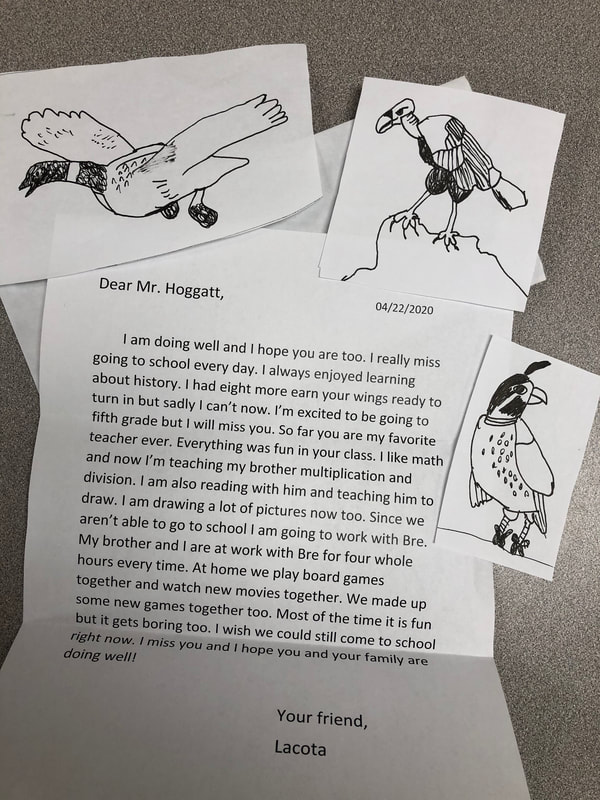

Each time I reread it, I also update it.

I walked through the cemetery of the enslaved on George Washington's Mount Vernon plantation and helped lay a wreath at the nearby slave memorial.

I stood on the spot where former slaves Dred Scott and his wife listened to a judge tell them they were still only the property of an owner.

I visited the birthplace and childhood home of scientist and educator George Washington Carver.

I stood in a parking lot, looking upward to the hotel balcony where Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and I traced the path of the bullet that killed him.

I drove down Florissant Avenue in Ferguson, Missouri, site of the 2014 race riots following a grand jury's decision not to indict a white police officer for his shooting of an African American.

I walked a street in Baltimore, Maryland, where I was the only white man among hundreds of people of color, only to be told by workers at the local tourism office that I should not be there and that I should return to my hotel room immediately. This was the same location for riots in 2015 in response to a black man being killed by police.

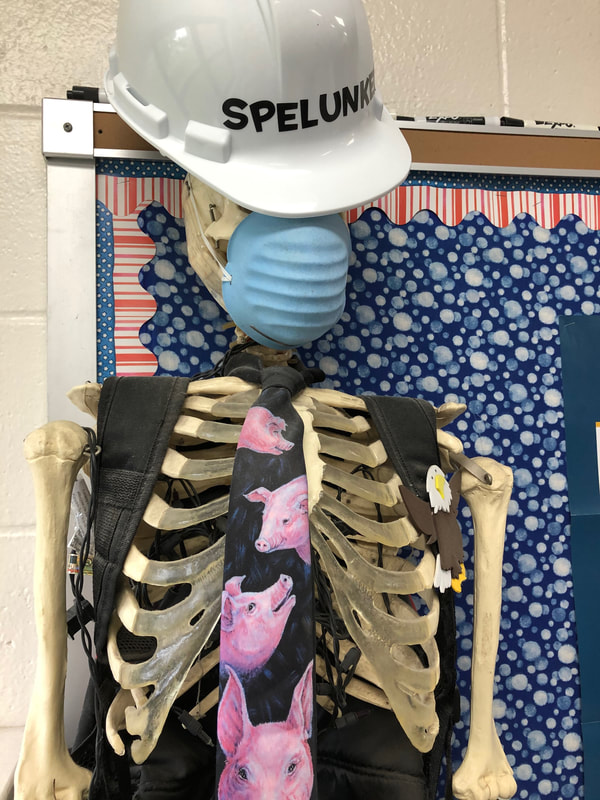

I spent a day in a predominantly-black school in Atlanta, especially paying attention to the school's culture and personality.

I visited the Springfield, Illinois, location of race riots that spawned the development of the NAACP.

I touched the stair rail in Abraham Lincoln's house and wondered of the emotion that compelled him to pen the Emancipation Proclamation.

I stood at the graves of Civil War soldiers from both sides and wondered at the reasons for their resolve.

I walked Civil War battlefields and forts in numerous states, marveled at the conditions of the situation, and imagined the blood flowing into the watersheds, the sounds of hundreds of muskets firing nonstop, and the smell of burning gunpowder. I touched cannons, muskets, bayonets, and cannonballs.

I strolled through the slave burial grounds at George Washington's Mount Vernon, and studied Washington's mindset toward slaves.

This summer, one of the highlights of spending a week at the Colonial Williamsburg Teacher Institute was going to be the chance to see the original site of slavery in America at Jamestown. That trip has been postponed for a year, so I still look forward to understanding more about the arrival African culture in the colony.

With all of the understanding (even the limited understanding that I have) of historical events dealing with racial differences, I still find it very hard to wrap my mind around what some people think is fair. We play with that word in class, as I try to make students understand that Life is not fair, but that we should try to treat other people with fairness. I cannot understand the desire for destruction that seems to keep returning to the major urban areas of the United States. In fact, I'm not sure the people who are involved in riots and protests understand everything either. Maybe that ignorance is the parent of frustration that leaves us all feeling helpless. Perhaps that is why people tend to congregate and go with a crowd as tensions rise.

No, I do not understand the idea of "live and let die", "kill for revenge, or hatred of any kind. I cannot comprehend tearing down my own house in protest of injustice, and I probably will never understand how that such actions will satisfy my frustration.

Instead, I try to understand my own responsibilities - the things I can control. I control my own actions and reactions. I know that it is acceptable to love myself without selfish pride, but that I must also love and respect my neighbor. I understand that I can be wrong, but that I can learn from my mistakes and make changes in my life.

I understand that facts, vocabulary, and speech content do matter. I believe that attitudes can be transparent, but that perceptions are not always true.

I know that I must avoid all forms of idolatry, whether in the form of sports, celebrity worship, material pride, or racism. I understand that people are bull-headed and difficult to positively persuade, while at the same time they are soft and easily tempted to engage in destructive activities. I am under the impression that I can easily to go along with a crowd in order to avoid conflict, but that in doing so I may cause another conflict. I know that I should treat other people the way I want to be treated. I know it is not as much the way I act, but the way I react to the hazards and detours in life that make me the person I am.

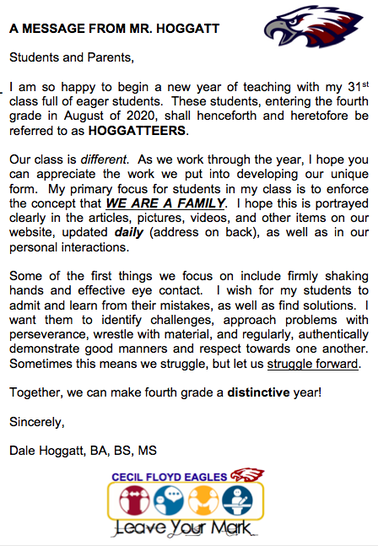

I must train my conscience to make the right decisions, train my children to do the same, and respectfully influence neighbors and strangers to adopt mannerly attitudes. I teach. I preach. I write. I speak. I engage the community.

But my struggle remains: that communication gap that I have with people who do not understand me. While I sit with a quizzical expression on my face, not understanding irrational racists, violent religionists, and disrespectful separatists, I must understand communication is a two-lane highway, and people often do not understand me either. I must continue to seek that dialog and understanding.

But how do we speak each other's language? How do we bridge the communication gap?

How do we understand driving emotion? Irrational fear? Uncontrolled anger? Raging hatred?

What part do I have to play? As a parent? As a husband? As a teacher? As a servant? As a man? As a Christian?

I visited Crazy Horse's monument.

I walked on the Trail of Tears.

I explored Anasazi ruins.

I climbed a Mississippian mound.

I danced with Sioux Indians in Colorado.

I visited the Cherokee Nation Headquarters.

I have walked with the Chickasaw.

But proximity does not always translate to understanding. All I can do is my best to treat people like people, brothers like brothers, and every human being like a member of the single, human race. After all, aren't we all just different shades of the same color?

Sometimes I don't know how to address my students around the topics of slavery, Civil War, Civil rights, and modern racial-charged accusations (sometimes as thick in the air as mosquitos). We look at history, we learn from the mistakes of others, and we try to understand even the most irrational. There are antecedents - causes, origins. And though they are ugly and sometimes irrational, they are important to understand. May we not be too shy or too fearful to learn about them, to learn from them, and not to physically distance ourselves from the realities of the past.