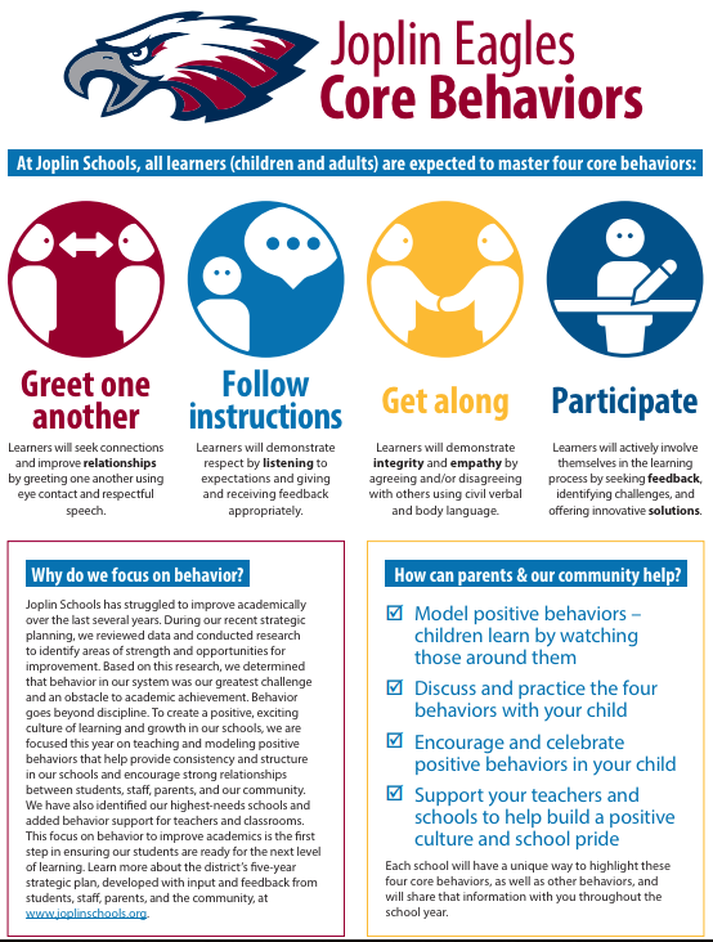

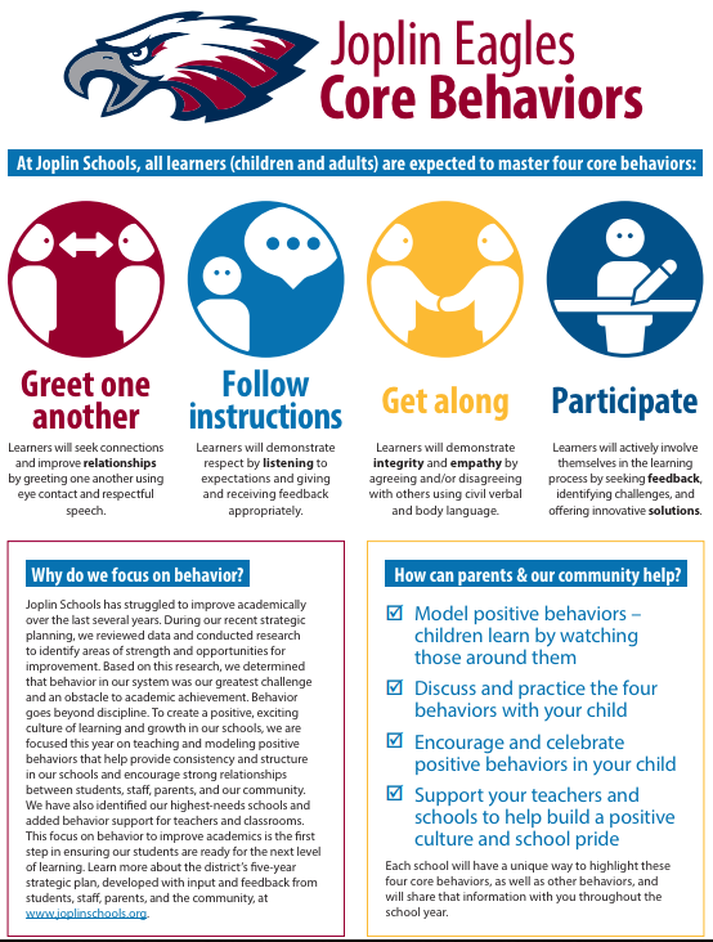

| At Cecil Floyd, we have embraced our school district's four Core Behaviors. We recognize the importance of these behaviors in society, so we want to do our part to prepare our students to face the future by emphasizing them. Last year, we began tracking our successes with these behaviors. In the interest of transparency, I figured I could publish the results for our classroom for the first quarter here. In the area of Greets Others, we do well with 94%. With Following Instructions, 83% of students in our room were successful. For Getting Along, 72% of my students scored as meeting or exceeding expectations. Tolerance and reacting to the movements and words of others have become a focus to help us with this. Seventy-eight percent of students were adequate of above average for Participating. |

|

Report cards will be distributed at this Wednesday's and Thursday's parent conferences.

0 Comments

I just discovered that the last principal I had in Oklahoma City passed from life, last spring. Gary Blevins was the principal at Buchanan Elementary School in Oklahoma City, when I was there, ending in 1995 - the year of the Oklahoma City bombing. Gary is the person who gave me more responsibility at the school, even naming me as lead teacher for my last two years there. He gave me decision-making authority, resulting in me being the person in charge of the school on April 19, 1995 - the person responsible for locking down the school when Timothy McVeigh detonated the bomb that killed 168 people.

The first thing Gary did when coming to our school was to repaint one wall of his office - John Deere green - and put pictures of tractors up. The office looked terrific. We had long, candid conversations in there and elsewhere about the school. He was preceded in death by his parents; his infant twin sister, Sharon Gwen Blevins; and a grandson, Logan Hodge.  1995 1995 Gary was not only an educator, but also a farmer, a deputy sheriff, and an auctioneer. It was his family that made him the most proud. I certainly came to appreciate Gary's worth ethic and his dedication to his wife. He frequently told me that he could not live without her. I hope that Mrs. Blevins is able overcome such a concept as she is now without her long-time husband. In 1995, my wife and I moved to Joplin, Missouri, and I had to say goodbye to Mr. Blevins. The last time I saw the man, the school had just received an irregularly-shaped piece of marble from the Murrah Building. Gary used the heal of his cowboy boot to knock off a small piece of the marble to give me. "You were the one who protected the school that day," he said. "You deserve a part of this." I've missed Gary for a long time, but his passing makes me miss him in an entirely different way.  There is a silent call for teachers to create Individualized Educational Plans for every student in the classroom - whether a student has learning disabilities, gifted inclinations, or neither. This will be entirely too cumbersome from a record-keeping standpoint, and will gum up the system so teachers have no more time for creative ventures (like lesson and project planning, for example). Yes, teachers must know the needs of their students, and yes, teachers should fashion lessons and classroom design to address those needs, but there is no need to get so bogged down in the swamp of data collection and individualized plans in order to get that done. I would call for a more balanced, "common sense" approach to empower our teachers (and students). I enjoyed reading these observations from Mr. Wyborney in his book, The Writing on the Classroom Wall: Adequately personalizing a lesson for each and every student is nearly impossible when I try to contain the personalization within my own abilities. However, what is possible is empowering students to seek connections between the content and their lives. Exactly! Wyborney hits the nail squarely once again. Teachers and students are not programmable in a strictly scientific sense, and yet, this is the result. The discrepancy between these ideas - humanity and programming - becomes a fault line that eventually shakes the spirit of the school.

The challenge remains. How do we still strike a personal chord with each student without creating even more uniformity? How do we foster personal relationships? This year, we want to work on uninterrupted classwide conversations. This is something new that I've implemented as a part of our regular schedule. I've also asked our administrators to observe us when we conduct some of these conversations. Students will be expected to follow the guidelines of our uninterrupted classwide conversations. They will:

The teacher will initiate a conversation. This will involve one of the following:

This process, if explicitly taught and practiced, should support other areas (i.e., academic, social, emotional). I would like to increase stamina and decrease interruptions in these conversations as the year progresses. I also need to get more students involved in the conversations (as there are some who like to dominate). As I have read the last chapters of Steve Wyborney's book, Writing on the Classroom Wall, I've also realized that I can apply some of his thoughts to student conversations. Wyborney finds value in giving the class the answer to a problem, removing that part of our expectations and placing more emphasis on process. In addition, Wyborney suggests offering problems with multiple solutions, broadening the conversation. I hadn't designed our uninterrupted classwide conversations with Steve Wyborney's words in mind, but it has been nice to see that his book supports many of the things we do. For more commentary about Writing on the Classroom Wall,

see my Professional Publications Commentary page. The Veterans Day program is less than a month away (Tuesday, November 7).

We will perform this program twice - once in the daytime and once in the evening. Eight students will have solo singing parts, including these incredible Hoggatteers: JOSIAH, CADENCE, and MACIE. Writing is extraordinarily powerful!  Thank you, Mr. Wyborney. As a writer, I have long believed that the Writing Process is a bunch of made-up mess. Unlike math and science, there is no set process to writing. Writing is very much an art, and as such, it should be acceptable for writers to select their own processes. I, too, believe there are some fundamental standards in writing as far as sentence construction and plot development are concerns, for example, but I would discourage efforts by instructors to provide too much guidance in the writing process. Wyborney describes the process by which he came to the conclusion that prewriting is overrated - or at least misapplied. Unfortunately, as I guided my students through a detailed writing process, I often found that the funnel of creativity seemed to narrow. The open-ended power of prewriting seemed to cultivate curiosity and creativity, and then the rest of the writing process seemed to mow it down to an unwanted uniformity. That phrase - "funnel of creativity" - resonates with me. Indeed, funneling creativity through smaller holes stifles it at exactly a time when it should be flourishing. As some point the prewriting must end. In fact, there are many times when I pass over any form of formal prewriting just to get something started. "Prewriting," I realized, did not take place before writing. Prewriting was not preparing to write. Prewriting was actually writing. Initially, I thought the different forms of prewriting...all shared a common feature: the recording of thoughts... Prewriting is something that I blend, in my own writing, into writing itself. Mr. Wyborney is quite eloquent in the presentation of his thoughts on the matter. Personally, I have never followed any three- or five-step process in my writing, choosing instead to blend the steps - somethings stopping to return to the beginning for editing and revising - made all the easier with the invention of the computer - sometimes stopping to think of options for the next portion of a story or the next chapter of a nonfiction manuscript. As I continued to write and to work with students, I eventually realized that the act of writing involves a massive intrapersonal exchange of thinking. The refinement of thinking is spurred on by recording thoughts (in any form), and those recorded thoughts, which may come in micro-moments, continually fuel and inform the thinking. You said it! Some of my best thinking occurs as I write, not before I write. The next statement is true, as well: No wonder I felt such a sense of dissatisfaction as I guided students toward mowed-down creativity that yielded highly similar products. I was failing to acknowledge an extraordinary process. How many times have I advocated for just about anything besides viewing our students and teachers as products on an assembly line? Too many to count. Rather, I wish for my pupils to produce high-quality, creative, and one-of-a-kind products. Why must they all write the same three-point paragraph about a particular subject? Why can't they use their independent voices to present their latest tale? For every student I squeeze (figuratively speaking), a different juice should drip out (Mayhaps that's not a great metaphor after all.). Actually, I don't have to change anything that Mr. Wyborney has already written when he says the following: As a teacher, I find that there is an unusually strong temptation to try to "make meaning for the students" by talking. Yet when I compare any attempt to "make meaning for the students" to the power of student writing, I have a difficult time making sense of any approach in which I spend a majority of the lesson talking. Once again, we tend to forget. In writing, I've struggled to develop what I know about other school subjects. In math, science, history, and reading, I keep asking my class to report about what they notice. I quickly also ask the class to identify what they wonder. But when it comes to writing, we often have a different approach. We forget to ask students to notice and wonder, and we fail to engage and empower them to blaze their own trails. I am learning to resist the temptation to make meaning for the students. I am learning to remove my voice from the conversation and to provide space for the students to be the makers of meaning. Wyborney goes on to observe that writing can come in shorter bursts of reflection throughout the education process. While there's usually not enough time in the day to write about every little thing, we have tried to address some of those thoughts through our daily (ish) blogging. We take notes throughout the day to support students' blogging, and they always have something on their minds to share with the world.

May we continue to see the steps of the writing process, but may we also understand that writers must apply their own quirks, eccentricities, and idiosyncrasies, and habits to their art!

It wasn't something I learned how to do. I just did it. And I think it makes a difference for students who find respectful responses less intuitive.

Say what you mean and mean what you say. The video above addresses this concept. It's a bit of a no nonsense approach. I must admit, I still say please, but my voice indicates that my request for action from my students comes with a different tone. No lilt at the end. My please comes with more of a command than question. I never ask someone, "Would you mind doing this?" A question like that makes it sound like the activity is optional. Keep it simple, I say. If what I want students to do is not optional, I need to make that clear. If what I want them to do is a required activity, I should not be using the word please. Again, please implies a choice. While we endorse good manners and respect, there is definitely a difference between a request and a command. I often hear teachers deliver instructions as if they are begging for compliance. They speak to children is soft, lilting voices, pleading with them to please do the work. Please. And soon they find themselves in negotiations with backtalking students. They respond to a child who backtalks, rather than address the disrespectful backtalk. They lower themselves to the level of backtalking the backtalker. What kind of citizens are we producing? I believe we do a disservice to children when we do not clearly communicate our expectations - with urgency when necessary, and with choices when possible.

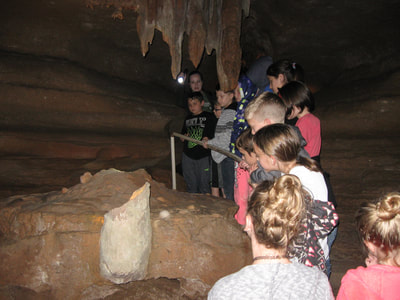

The Browning Museum boasts an extensive mineral and rock collection that our students were able to enjoy and appreciate in Friday's field trip to Bluff Dwellers Cave. Kathleen Browning, daughter of the cave's discoverer Arthur Browning, purchased and collected the items in the museum (which is free to the public). There are some large and beautiful specimens in the cases here, mostly locally mined. Students appeared to appreciate the collection, even taking the time to listen as one of the employees cranked up the Edison phonograph, hold a heavy cannon ball, and marvel at the old toilet seat. One student stood oh-faced in front of an antique device. "Oh, wow!" he exclaimed. "I always wanted to see a real typewriter!" The arrow- and spearheads on the walls here were collected mostly from the property on the other side of the highway from the cave. Later, we would discover that our cave was visited often by the ancient, indigenous people in the area. These people left their calling cards in the cave in the form of a couple of grinding bowls (on display inside the cave). Stay tuned for our cave interior photos (coming soon).

Watch for more photos from our trip in the next few days.

We saw some visitors in our classroom yesterday. Miss Wilson and Mr. Trueblood, our newest teachers in the fifth grade, came to our room to observe classroom management. Afterward, they stuck around to interact with students. What did they see?

As we progress through multiplication and prepare for working more complicated, multi-digit problems, we continue to test multiplication fluency. Our students are pressed to work 100 one-digit multiplication problems in 5 minutes. We wish for them to overlearn the facts in preparation of other Math applications that will also require the skill.

CADENCE is the first student to successfully complete all 100 problems in 5 minutes, proving her mastery three times to earn the title of Multiplication Master. A couple of others are right on her heals. Our class still has a deficient average as a whole, but most members made improvements, last week, with some of those being significant gains. I'm not one who continues to push students at the beginning of the year until we move past the skill; instead, I like to move steadily throughout the year. I believe in doing so, the momentum continues and the skill sticks much more effectively. Parents who choose to help at home are certainly encouraged to do so. Congratulations, CADENCE! We have finally formed the 2018 Cecil Floyd Math League,

and four Hoggatteers made the team! We want to congratulate RAHAF, CHRISTIAN, CADENCE, AND JORDAN. This year's qualifying contest will be held at Joplin's Thomas Jefferson Independent Day School, on January 20. Reading is thinking. Reading is about making meaning.  Sometimes educations tends to compartmentalize or departmentalize learning. For years we have followed a model that moves through periods of time where one subject is taught in isolation from others. That system is not necessarily the most effective. In The Writing on the Classroom Wall, Steve Wyborney touches on an idea in reading instruction that teachers would do well to consider - that reading does not always manifest itself during reading class. Reading shouldn't stop with the school bell. When we read, we are doing so much more than just recognizing letter sounds. ...[Y]ou are the one interacting with the words and ideas, referencing them to your personal context and paradigms, and comparing them with many other factors. You are building layers of agreement (or disagreement), sensing possibilities, wondering what this might look like in your classroom...You are visualizing, interpreting, contemplating, and conducting myriad other acts associated with the wonder of reading. Whew. We have to recognize that there is more going on with reading than phonics and fluency. As such, it might just take a while before some of those skills kick in. We've all been there - at a time when we suddenly understand that joke, or we suddenly figure out how to work that equation, or we suddenly remember that dream. Wyborney ably explains: Sometimes the power of reading is found in between these moments, when the student simply says, "hmmm..." and her eyes drift away from the text in deep thought about the ideas that are churning. Sometimes the power of reading is found the next day, or the next week, or even years later when she actually sees "two roads diverge" and wonders a little more deeply about the choices each one might lead to. Now there's a connection that means something! It's not just words on the page of a teacher's book.

I have long realized that combining skills is a more efficient method of disseminating information. That's not to say that we sacrifice quality for quantity in our instruction; it is to say that when I can make connections between standards and problem solving, reading and science, history and math, it means something more to my students. When they can see the meaningful connections, they pay better attention and they retain the information better. |

AnthemThe Hoggatteer Revolution

is an extensive, award-winning, inimitable, digital platform for Encouraging and Developing the Arts, Sciences, and honest Christianity in the beautiful, friendly LAND OF THE FREE AND THE HOME OF THE BRAVE This site is described as

"a fantastic site... chockablock full of interesting ideas, hilarious anecdotes, and useful resources."

...to like, bookmark, pin,

tweet, and share about the site... and check in regularly for new material, posted often before DAWN'S EARLY LIGHT! History in ResidenceElementary Schools: Bring Mr. Hoggatt into your classroom for a week of engaging and rigorous history programming with your students. LEARN MORE BUILDING BETTER

|