| I was kindly asked to participate in an interview for the Crystal Bridges blog. I'm sure the folks there will trim it, but below is the conversation as I recorded it. |

DH: I started teaching in 1995 (Do the math.). I taught first and second grades for five years in Oklahoma City before moving to Joplin, Missouri. I have since taught in my corner, fourth-grade classroom. At the end of this school year, that will be 27 years in Joplin and 32 years total (Check your work: was your subtraction correct?). I’ve been the Teacher of the Year for Joplin Schools and have received other awards for my performance in the classroom.

I plan to find opportunities to continue supporting education. I would like to provide professional development to teachers and schools, work with new teachers and student teachers, and develop lessons and lesson sets. I just completed orientation with the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, headquartered in New York City, and hope to work with them on some incredible projects. My relationship with GLI comes as a result of being named Missouri’s 2021 History Teacher of the Year.

CB: Do you teach a particular subject or all core subjects?

DH: Yes.

Actually, our teachers prefer to keep self-contained classes, so we teach all of the core subjects. In the past few years, I have developed my expertise in math and history (There aren’t many elementary teachers who can claim to specialize in history, so I’m pretty unique in that.). Working with history and art is a natural fit, and in my class we look at a lot of art from the colonial and revolutionary eras. From the beginning of my relationship with Crystal Bridges, I have pushed for a focus on art from the 17th and 18th centuries.

CB: When did you first visit Crystal Bridges?

DH: My son and my wife beat me to it. I think I finally got around to visiting in the summer of 2017, on a whim. It seems we were in the area for some other reason when we had a little extra time, and I suggested we visit Crystal Bridges. I was instantly impressed with the collection and presentation, and pressed forward with getting my peers to take a field trip during the following school year. During the summer of 2018, we all participated in a summer residency and teacher institute at the museum.

CB: Tell us about your first summer residency at Crystal Bridges. How long were you there and what did you learn?

DH: My grade-level teaching team entered a partnership with Crystal Bridges, and we were able to spend a week at the museum, in the summer 2018. We were quickly immersed in methods of interpreting art with students. On one day, we were able to highjack one of the museum educators (who would probably prefer to remain nameless) and take a private, extended tour of the museum. During that tour, we practiced some of the skills we had learned earlier in the week.

The residency challenged us greatly in some unfamiliar territory. My own teaching was reinforced and affirmed during that week in Bentonville. I was already beginning to incorporate art in my history lessons, but now I had the tools to present it more effectively. It allows me to do so with academic rigor and more understanding than before. Every student in my class is now able to enter the conversation and add something vital to the lesson. Their observations and engagement with real art helps them understand the events of the era, the lifestyles of both the gentry and the common person. We now consider the enslaved, the natives, and the women of the era, in addition to more traditional stories and heroes in history. Using art as a stepping stone, we can connect multiple points of view to our present era, as well.

CB: What other projects or partnerships have you been involved with since then (with Crystal Bridges)?

DH: In the last 10 years, I have discovered the best professional development of my career. It started with the teacher institute at Crystal Bridges. During the same summer, I was accepted to the teacher institute at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. I stayed on the property at the Washington’s mansion and tomb for a week and studied General Washington at War. The following summer, I was one of 12 educators to travel to Fort Ticonderoga in Upstate New York. We spent a week discovering “America’s Fort” and the lifestyles of soldiers during the French and Indian War. We also compared and contrasted the French and Indian War with World War I. Art played a prominent role in each of these historic experiences, and I found what I had learned at the institute in Bentonville, Arkansas, to be quite helpful.

Our partnership with Crystal Bridges has also continued since my first summer experience. We have hosted a museum educator in our classrooms for a week each year since, and we have taken our classes to the museum each year for field trips (virtually in the spring of our 2020/1 school year). Students have connected with the Crystal Bridges collection – appreciating the details, reacting emotionally with the art, writing about specific pieces in meaningful ways, and creating their own artwork in response. Others have visited for field trips, but our partnership has fostered a deeper connection with specific artwork and installations as well as museum staff and educators.

CB: How many of your classes have experienced field trips at Crystal Bridges?

DH: By my reckoning, five classes have attended field trips to the museum, but last year was a virtual presentation.

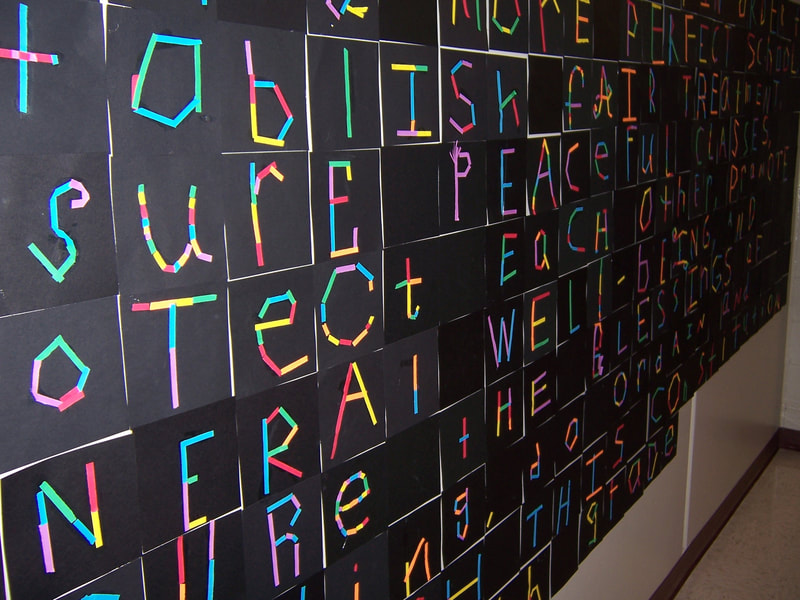

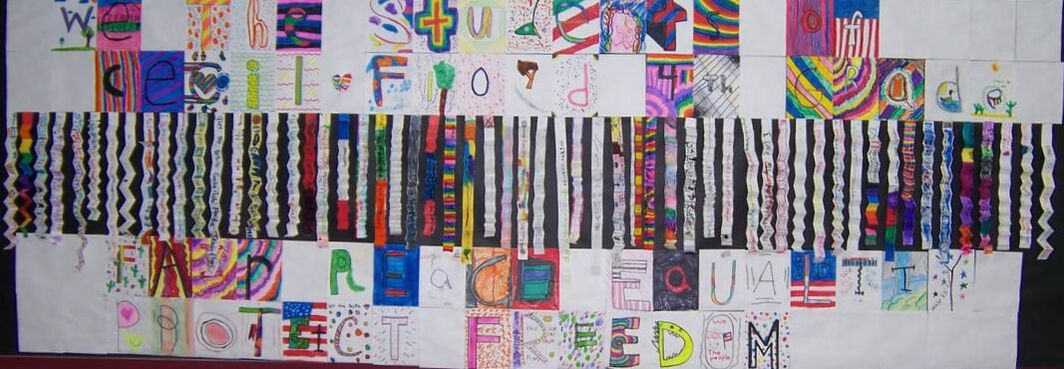

| CB: I noticed on your blog that your class earlier this year created an art project inspired by Nari Ward’s We the People. Did you come up with that assignment? What did the students learn from it? DH: Actually, our classes have responded to We the People almost every year since we began, but these specific projects have come from our artist-in-residence. On our first visit, in passing, we witnessed the piece being installed in the colonial gallery. |

During a different year, each class used paper shoestrings to make the letters in a different word (Our word was FREE.).

Last year, our four classes collaborated on a short version of a Preamble, decorating and folding paper shoestrings to fill in the center of the project.

DH: My job as an educator is to get students engaged. When children are engaged with the content, they also bear some interest in it. I have learned not to “give” my class answers without first hearing about what they notice and what they wonder about a piece of art I present to them. They quickly learn that there is nothing too small to point out. They also make inferences by putting the information together and talking things out. In fact, I find myself teaching reading comprehension, literacy skills, and historical thinking by using art instead of text. In this way, they learn to think deeper even – even when they don’t read on grade level.

The truth is, I use these same methods for math story problems, reading texts, science experiments, and history lessons. I use them with photographs, as well as primary documents and documentary videos. Students in my class can hold conversations on just about any subject, and they usually begin with art.

CB: You have posters of artworks from Crystal Bridges hanging in your classroom. How have you found it beneficial to include these in your teaching?

DH: I don’t want to sound repetitive, so let’s talk about the décor of my classroom. First, it changes throughout the year as we progress through history. I use many posters that include depictions of our founding documents, early surveys and maps of the colonial era, and art. Photographs do not exist from the 17th and 18th centuries, so art in many forms comes into play. Students can see the setting for many of the events, as well as fashion trends and the ways of life. Both the famous and the common man are depicted in the décor. Instead of laminated, cartoony posters with cute labels, I like to put classic art on my walls and bulletin boards. Students and their parents respond to this different setting. Our classroom boasts flags from a different time when appropriate to the study.

Then, when we visit Crystal Bridges, students see things with which they are familiar. I like to think they react differently than classes that are not as familiar with the methods and the appearance of the museum – especially within the eras they have been studying.

CB: Have you seen any changes in the way your students think or respond to class curriculum based on their interactions with Crystal Bridges?

DH: My students now boldly step up with their observations and inferences. They are not scared to present their ideas about artwork or other items, and they learn how to disagree and ask questions to glean clarity from their classmates.

They often find things that I haven’t considered, and they put details to work in their conclusions. They learn to “stay within the four corners” of a piece of art and to back up their conclusions with the observable facts presented by the artist. They cite the item before them instead of basing their conclusions on wild guesses or assumptions. This is rich – not just kids trying to repeat what the teacher has fed them, but kids getting their brains engaged and responding with civil discussion.

That all sets the foundation for the rest of the lesson, and now that my pupils have safely entered the conversation, they can stay for the newest information and skills that I need to present to them. They are invested enough to desire more from me in the presentation, and they are more willing to put forth the effort necessary to perform tasks to accomplish their academic and social goals.