History is just the memorization of people, places, and dates.

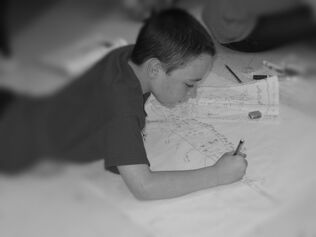

Map Making

Map Making - Focus more on the overarching ideas. It is not important to have a knowledge of specific dates, but to be able to easily find those dates. It is more important to have a good understanding of how events fit together. Teach your students to follow a progression of events, both with a close view of events in an era, but also with a longer view of events across eras. Likewise, specific names and places don't have to be memorized only to be forgotten after the test. Students are better served by getting an idea for who the people were and what happened in the places in question. They should know them well enough to recognize them in conversation. They should be able to find the locations in a general area of a map, but there really is no need for them to label a blank map with a list of place names. I know there could be some pushback on this from educators with different points of view, but I propose that the blending of events and ability to discern what really happened during historical events is the more relevant study. If my students can understand the cause-and-effect of societal, governmental, and individual actions, they will become better citizens in the present and, hopefully, in the future.

- Focus more on perspective - the timeline. I've covered the concept of timeline in past mythbusting articles, but the subject fits below this myth, as well. Events taught out of context are really pretty meaningless if they are not relevant to today (See below.). In order to do that, the teacher must connect the dots between events. That might mean we work backwards from the current 50 states. We have statehood in 50 states because of Manifest Destiny, right? But Manifest Destiny was only a dream at one time. How do those dots get connected. An educator might draw lines to gold rushes in California, Alaska, and Colorado. He may draw more lines to westward trails to California, Oregon, and New Mexico. Another line may trace a path to Utah with the Mormon migration. Before all of that, however, came mountain men and other explorers including that Jefferson-sanctioned Corps of Discovery with Lewis and Clark, which resulted from the Louisiana Purchase. The groundwork for which came through the Jefferson presidency as a product of Spanish and French ownership of the territory between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. It could get quite complicated, but if you can put it on a timeline or describe the progression, students can better see the consequences and rewards of a series of actions. Things don't just happen on that timeline: people made them happen. Every label on the timeline is the result of people's responses to prior actions over time, creating a smooth trend out of some very rough events along the way.

- Focus more on growth mindset. I saw an article about Auschwitz. It explained that over 1.1 million Jews were slaughtered there, but that the place still stands today, because the Jews wanted it preserved, not as a salute to the Nazis, but as a reminder to never let such an evil happen again. Growth Mindset is the idea that anyone can learn. More importantly is the concept that we are going to make mistakes as we press forward, but that we should learn from those mistakes and not push them aside to forget them. It is the idea that if you fall off of a horse six times, you have to stand back up seven times, that you don't give up. But you also don't get stuck in a loop, futilely trying to do it the same wrong way every time. I like to tweak my lessons from week to week and year to year. I like reevaluating how I do things, fixing the things that didn't work and enhancing the things that did. Can we get students to have that same mindset? Will they ever see the value in studying the horrors of history in order to improve present and future? Can they put themselves into the shoes of the people making such decisions in order to understand the complexities of change? By doing so, perhaps they can see value in pondering monuments they don't understand. Maybe they can appreciate opposing points of view and can better respect the reason a statue was erected, rather than try to erase its offensive presence. Maybe, just maybe, they can see the reasons a person fought on the wrong side of a battle and see that a piece of stone or lump of bronze does not always indicate that we idolize the person in the effigy.

Murrah Federal Building, Oklahoma City, 1995

Murrah Federal Building, Oklahoma City, 1995 - Talk more about relevance - connections. Again, I've written about this before, and I will again, but it's worth repeating now. It goes with the timeline bullet above, where I wrote about history affecting us today. That can be difficult for a teacher of youths - difficult because, well, how do make the attack on Pearl Harbor relevant to a kid who would rather be playing with his Lego blocks or Playstation? How can you relate something that happens in 1941 to a kid living in the 21st century? Often, I create a parallel to schoolyard bullying or the faceless comments on unsocial media. When I present my personal experiences during the 1995 bombing in Oklahoma City, I always bring events around to the subject of civil discourse. I tend to look at my fourth graders and catch the realization of the connection on their faces when they realize what the destructive power of hatred can become.

- Get kids thinking critically. There is a message in Louis Sachar's book, There's a Boy in the Girls' Bathroom, where the counselor tells concerned parents that she doesn't believe in telling kids what to do, but prefers to help them make strong choices on their own. I realize that students need wise guidance, but I also like that message. Whenever possible, I allow my students to do things incorrectly with the intention of also allowing them to find the problem and solve it on their own or by utilizing the power of a cooperative group or other resources. But critical thinking goes beyond just making more mistakes; critical thinking involves being faced with a choice and making decisions based on proper evaluation of the choices. Both roads may lead to the same conclusion, but which it better? Both methods may solve the same problem, but what is the cost analysis? Where do we draw the lines or morality? What opportunities are sacrificed? How will my decision affect others? Can I live with the choice I make? Will it be dangerous? These are truly life skills, and they fit in the history setting better than in other subjects.

Valuable Conversations with Peers and Adults

Valuable Conversations with Peers and Adults - Come on! It's too easy to write tests about dates and names. The bottom line is that multiple choice tests are easy and fun to write. They are also the easiest to grade, and that, more than for any other reason, is why we like to use them. Teachers are no different from other people: we like to save time and effort. There's nothing wrong with that, but it's also just an excuse that leaves us in the mud of rote regurgitation of low-order facts. If we want to produce better citizens, we must be able to move past the easy evaluation of students and shift to more important discussions. I'm not even sure those end-of-unit tests and endless data collection are very useful anyway. I'd much rather keep things in conversational context - a classroom version of casual conversations they will face when they become adults and are talking around the watercooler or in the church foyer. I'd rather practice those debates with rich, robust command of reason than fill in bubbles on a scantron. I could do that every day. In fact, we do, and my fourth graders really get involved. Why? Because I respect them enough to listen to them, and I teach them to do the same for their peers.

We find ourselves sitting at a point where people choose to act violently on every offense and every point of anger and disagreement, rather than coming to the table, looking the opponent in the eye, and have a discussion. Maybe that will be a positive end result of present conflicts. It would be nice to be able to skip the destruction and go straight to the conversation, wouldn't it? That can only happen if education gets on board with teaching history up front and not poking in a pile and calling it non-essential.