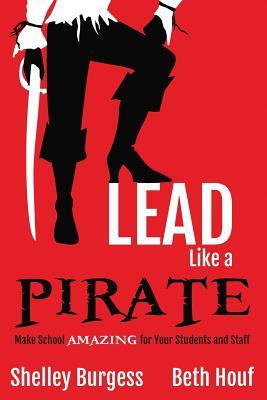

Programs don't teach kids; teachers do, and teachers are capable of making magic happen for kids. The solution to any school challenge or issue is never just a new program. It is a commitment to the people who are doing the work. It is building a sense of self-efficacy in the individuals on your team and convincing them that the magic isn't in the latest initiative or curriculum mandate - the magic is in them. That's a quote from Lead Like a PIRATE, by Shelley Burgess and Beth Houf, and it's really hard to disagree. In this particular chapter of the book, the authors are all about heralding teachers and respecting them by giving them permission to make professional decisions. Some teachers wait for that permission, and others rebel more openly until it comes. |

Programs are handed down from decision-makers at the top, and principals are expected to enforce "non-negotiables" with their staffs, knowing full-well that the program will not work without complete buy-in and ownership. Some of us don't work well with a script or a full program. Shelley already knew this, but during her first years as a principal, she had a taste of what it was like to be the person in the middle:

During my (Shelley's) first year as principal, our district had just adopted a new reading program. The mandate at the time was "fidelity to the core." (That phrase seriously still causes me to break out in hives!) I recall being completely taken aback when, during my interview for the position, someone asked how I would hold teachers accountable for to following the program exactly as written. The concept of cookie-cutter teaching goes against everything I believe in, but I must have come up with a good-enough answer because I got the job.

I like her admissions in this section - her descriptions of being stuck between bosses who expected perfect implementation and teachers who probably had the skills to keep the baby and throw out the bath water. Just like their students, teachers are different. When administrators or so-called educational "experts" tell teachers to differentiate their learning, but ignore the idea of differentiating teaching styles, they really are not experts at all. In fact, some might call them hypocrites.

Not me, of course. I would never do that.

But I don't know that these authors even fully expressed that particular sentiment in the book. They still wholly focus on the student, and do not openly address teacher differentiation. They do give hints in that direction, but I wish they had just flatly stated it to the people who need things outlined clearly in triplicate.

It involves knowing the unique learning needs of each child in the classroom and developing strategies to reach them and help them thrive. It involves grit, determination, persistence, flexibility, an element of fun, and a whole lot of heart! No program has that kind of magic, but teachers do. Believe in them, invest in them, build in time for learning and growth, and watch the magic happen.

In a previous chapter, the authors describe the time that it takes for educators to plow through top-driven, program-heavy expectations from above. Granted, they include many of the things that teachers impose upon themselves as well, but here is a major result of depending on "magical" programs to cure the maladies of a district. Teacher fatigue and depression will always be a problem when those teachers do not demand and receive professional respect.

We have all heard the saying that if we try to do too many things, we are not doing any of them well. This truth plays our all too often in education. If you are going to find educational treasure, you need to identify what matters most - you have to know what you are searching for and then be relentless in you pursuit of it. Spend the majority of your time working on obtaining it.